IMACS’ Director of Curriculum Development, Dr. Ted Sweet, discusses the importance of challenging the gifted and talented student in order to reach his or her full potential and to avoid common pitfalls. Ted is a graduate of Project MEGSSS, a predecessor program to IMACS. He completed his undergraduate studies at the University of Miami and his Ph.D. in mathematics at UCLA. Ted joined IMACS in 1998.

Burt Kaufman, one of the foremost American mathematics curriculum developers of the last half-century (and my high school mentor), once made an observation that resonates with many educators of bright and talented children. It was that good grades obtained through little or no effort ultimately led to poor study habits and general intellectual laziness.

Even parents of children enrolled in “gifted” programs of the type currently in favor with many public school systems sometimes complain that their child is “coasting” at school.

Unfortunately, students that solve every problem with ease often get out of the habit of focusing and thinking systematically, skills they will need if they are to reach their full potential. Not surprisingly, it can be a challenge for parents to explain to their bright children that getting an ‘A’ may not be enough to ensure their future academic success.

Bright students whose mental agility and intuitive cognitive abilities are not sufficiently challenged can start to develop problems during elementary school. These may manifest themselves in the form of so-called “careless errors” when doing arithmetical problems, for example. And talented students who have not been stretched intellectually will typically “give up too easily” when they finally encounter challenging problems that require careful analysis. In extreme cases, behavioral problems may start to develop.

The question of how to satisfy the intellectual needs of bright and talented children has been studied in depth by the professionals at IMACS. Our research demonstrates that bright students who are exposed to curricula that foster the careful, logical analysis of significant math problems benefit in many fields outside mathematics. A student who learns to truly think does not leave that skill in the classroom.

What classes that you coasted through do you wish had been more challenging for you?

Challenge yourself to be your best with IMACS. Take our free aptitude test. Follow IMACS on Facebook.

The A/C is cranked and the sweet tea is flowing. Our IMACS Hi-Tech Summer Camp, where kids solve logic puzzles, build electronic circuits, and learn how to program, is in full swing. Summer has definitely arrived at our headquarters in sunny South Florida. Did you ever notice how people from other parts of the country refer to it as “Southern Florida?” Wonder if they say “South California?” Anyhoo, we asked three members of our IMACS family to share their favorite math- or science-related books and movies for our completely informal, very unofficial recommended summer reading and viewing list. They say you can tell a lot about a person by the media they consume, so here’s your chance to get to know Lisa Cunningham, Danielle Ernst and Stephen Flegg.

Lisa Cunningham, Director of Curriculum Training

Lisa has an Ed.D. in Curriculum and Instruction from Florida International University and worked many years ago for us as a part-time math enrichment instructor. In our search for someone to head up our ISLAND training, we called Lisa to see if she knew anyone who would be interested. After hearing the job description, she said “What about me?” Lisa jumped at the opportunity, and we are so lucky she did. She also has a daughter who takes math enrichment with us.

Her survey response is below:

“Sure, I’d be happy to participate! I love all things Star Trek because it’s fun to think of what the future could be like, and it is all about the science of things – carbon life forms, tricorders …

I also really like Good Will Hunting. What I like about that movie is that it portrays a brilliant mathematician who would have attended a Title 1 school where, unfortunately, there aren’t as many enrichment opportunities available to foster intellectual and academic growth. As a teacher, it is rare to come across that natural ‘genius’ student who has not been exposed to such opportunities.

As far as books, I would recommend The Science Book. It has some great explanations and wonderful pictures. I use it to reinforce concepts with my daughter or to help her understand the ideas she questions.”

Danielle Ernst, Senior IMACS Instructor

Danielle was an IMACS student from 3rd grade through her high school graduation. During high school she also worked part-time as an IMACS office assistant. Danielle received her BA degree in Mathematics from The Johns Hopkins University. Upon graduation she contacted us about the possibility of working for IMACS and has been with us full time for the past two year. Danielle teaches many of our advanced math enrichment classes as well as our computer programming and virtual robotics classes. She is also involved in developing our new online Virtual Robotics Lab software. There’s nothing like hiring former students. 🙂

Her survey response is below:

“I’d love to be part of the blog! My favorite math book is called An Imaginary Tale by Paul J. Nahin. I read it right after I took a complex analysis course while I was studying abroad in Australia. My professor there was so enthusiastic about the subject that I couldn’t help but enjoy it as well. I found it extremely interesting to read and learn about about a branch of mathematics that only exists in the ‘imaginary’ sense.

My favorite math-related movie is probably A Beautiful Mind. It’s a very moving film with great acting, and it is based upon a real-life mathematician. It was a very popular movie, and I like that it brought a story about mathematics into the mainstream. Now people who never took any math classes after high school know who John Nash is, and so do I!”

Stephen Flegg, Senior IMACS Instructor

Stephen started teaching for us part-time in 1999 right after he received his BS degree in Physics from Florida Atlantic University and is now on our full-time staff. He teaches our most advanced math enrichment classes and also developed a beginner chess class for our homeschool program. This summer, in addition to teaching the electronics class for our summer camp, Stephen is involved in writing lesson plans for ISLAND. We’re very fortunate that many of our instructors such as Stephen love teaching for us and have been with us for a very long time.

His survey response is below:

“I found it tragically difficult to find some work that would be held up above another as my favorite. In the book category I can give you two books, the first being The Black Cloud by Fred Hoyle; yes, the same Fred Hoyle who made fun of the Big Bang with the name ‘Big Bang,’ and the name then stuck. It is an old novel but very well done and falls into the hard sci-fi genre. Although he takes cheap shots at the Big Bang theory and, by doing so, messes up the theory of evolution, the rest is solid. Those sound like major flaws but not in the context of the story. The next book is called The Age of Wonder by Richard Holmes. This book is a biography of the intellectual history of the 18th and 19th century. I haven’t finished it yet, but I’m loving it nonetheless.

As for movies with math and science, there are many but one seems to always come to mind – 2001: A Space Odyssey by Stanley Kubrick. I was very young the first time I saw the movie, but even at a young age I recognized the attempts to make it realistic even if I had trouble following the story. This became even more obvious when compared with Star Wars, which I also loved as a child. No sound in space, centrifugal force, orbits and many other features awed me then and now.

I was and still am a huge fan of the show Connections by James Burke. It been over for more twenty something years but it is still great.”

Lisa, Danielle and Stephen – thanks for sharing! You’ve given our fans a lot of good stuff to wrap their minds around this summer. Do you, dear reader, have a favorite math- or science-related book or movie that you would like to add to the list?

Add IMACS to your list of top picks. Sign up for our free aptitude test. Follow IMACS on Facebook.

IMACS’ Senior Curriculum Developer, Edward Martin, recalls a lesson learned from his own father about the virtues of honing one’s mental agility with games, an exercise that is particularly effective for developing abstract thinking skills.

When he was in a reflective mood, my dad occasionally revealed interesting episodes from life as a younger man. He recalled, for example, for several years riding the train to work in company with two fellows who spent the hour-long journey either with eyes closed or staring into space while sporadically uttering cryptic phrases such as “D five to B six.” Puzzled by this behavior, after a few weeks my dad asked them what they were doing. It turns out that they were playing chess…without a board! The amazing thing was that they were usually able to agree upon the outcomes of these wholly-imagined contests.

Few of us are blessed with such powers of concentration. However, the ability to concentrate is something that can be trained. As with many such faculties, it improves with use. Even 8- or 9-year-old youngsters are capable of feats approaching that of my dad’s glassy-eyed chess-playing companions. Next time your energetic third or fourth grader is acting up in the car, challenge him or her to a game of tic-tac-toe…without the board. Brush aside any incredulity that such a thing is possible. Just jump in and say, “I’ll go first. I’ll be X and I’ll put my first X in the top left corner.” Before you know it, your recalcitrant fellow traveler will be caught up by the spirit of competition and will be totally focused upon the goal of putting you in your place for having the temerity to issue such a challenge.

In this quick and simple little exercise, you achieve: honing concentration skills, thinking about and communicating grid-based information, and peace and quiet. It’s a win-win situation!

What are some of the mind-stretching games that you play or played?

Have you imagined yourself taking an IMACS course? Sign up for our free aptitude test. Play along with our weekly IMACS logic puzzles on Facebook.

Guest blogger and former student, Natasha Chen, shares her experience on parenting a mathematically precocious child.

First, this is not a blog about how to tell if you have a mathematically talented child. There are many great resources out there by people more educated on and experienced in that topic. (I’ve found the Hoagies’ Gifted Education Page, and the book “Developing Math Talent” by Assouline and Lupkowski-Shoplik very helpful.) If you think you have a mathematically gifted preschooler, then you might have discovered that it’s hard to find a program for gifted children that caters to this age group. These are just a few tips I’ve found myself sharing with other moms of three- to five-year olds that you might also find useful.

Building Sets

LEGOs, Tinker Toys, Lincoln Logs, K’nex, Magna-Tiles, tangrams, blocks of all shapes and sizes. All of these and similar toys are great for stimulating different areas of mathematical thinking at different stages of childhood. First, you can play all kinds of sorting games. Group the red pieces over here. Group the square pieces over there. Oh no, what do we do with the red squares? We can put them in the middle! All the rest go on the outside. Voila, introduction to set theory. Then there is visual-spatial reasoning. Have you ever observed a preschooler building a structure? She’s often down on her hands and knees looking at it from this way and that way, trying to figure out where to put the next piece. Seems like a pretty good way to encourage the ability to envision objects from different angles. And a message to parents of gifted and talented girls from a former girl: We love, Love, LOVE these kinds of toys!

Mathematical Logic

This can sound so daunting at first. “How do you expect me to teach mathematical logic to a four-year old?” The answer is that you probably already do it every day without realizing it. Does this sound familiar:

Dad: “Your mom and I don’t play with the crayons, so either you or your brother drew on the wall.” Child: “Not me!” Dad: “So who was it then?” Child: “He did it!” Wait, wasn’t that just [(P or Q) and (not P)] implies Q?

Or how about this one:

Mom: “If you want me to take you to the park, you need to sit down and finish your lunch.” Child is still running around. Mom: “Okay, I guess we’re not going to the park.” So now we have [(P implies Q) and (not Q)] implies (not P).

Or worse yet:

Dad: “We’re cutting out junk food in our family. We all need to eat healthier.” Child spies Dad sneaking some barbecue potato chips. Child: “Hey, you said we couldn’t eat that!” Dad: “Uh, I’m not really your dad, so I’m not in the family?” Busted!

See, logic is really the underpinnings of childhood discipline. Hmm, let’s leave that one for a different blog.

Fractions

I’m sure we’ve all said something like this to our kids: “You can have half the cookie now and save half for later.” And then you wordlessly break the cookie in half in view of your child. If you cook or bake, let your kids observe and narrate as you go: “We need a quarter teaspoon of salt. Would you please pass me the quarter-teaspoon?” “Which one is it?” “The one that says one and then a slanted line and then a four.” “Why does it say that? Why did you call it a quarter? That’s a coin.” There’s nothing like parenting gifted children to keep you on your toes! If your child’s fine motor skills are pretty good, then get a plastic knife and let them cut up soft ingredients. Say, “Cut it in half, and then cut the halves in half so you get quarters.” It doesn’t matter if they cut accurately, just that they comprehend that we get fractions from dividing up a whole. Keep a set of measuring cups in the bath toy rotation, preferably ones with the amounts (e.g., 1/2) written in big numerals. If you have room, keep several sets so that you can take one cup of water and pour it into three different 1/3 cups. “Look at that! The first cup is empty now and the other three cups are all full.”

Lose The Lecture

As you have similar kinds of enriched dialogue with your little Fermats, keep in mind that at this age there is no need to make a big production out of any of these lessons. Little ones generally don’t have the patience for a mini-lecture, nor do they seem to really embrace new information delivered that way. Mathematically gifted and talented youngsters will welcome these experiences as part of rhythm of their lives. It just takes a little more conscious effort on our part as parents to disguise the learning as play.

If you have any more tips, please leave a comment. I could use all the help I can get!

Start the ball rolling with IMACS by taking our free aptitude test. Follow IMACS on Facebook.

As news reports will remind you daily, education today in the United States is facing some of its most serious challenges. While extracurricular activities like music, art, and physical education were the focus of past budget cuts, the more recent crisis is taking aim at classes for advanced and gifted students. The Wall Street Journal recently published an article about Advanced Placement students taking courses online after the traditional AP classes were cut from their schools. So if you find yourself seriously thinking about online classes for your child, whether out of necessity or choice, how do you get the appropriate credit at his or her school? The first challenge is to find a quality program with quality people. You’ll see why this matters beyond the obvious reasons as you read the below advice that we give to the parents of our students.

Officially approved course. Whenever you are trying to establish credibility for someone, it helps to have someone who already has credibility vouching for that person. That’s why in a courtroom, some people make good character witnesses, and others, not so much. It works the same way with online high school classes. Teachers and administrators just don’t have the time or resources to review in detail every program that is presented to them for consideration. So it helps if they can look to an authoritative body that has already done the analysis. When the College Board, for example, audits an Advanced Placement curriculum and lists it on their Web site as an approved online course, you know you’ve found a program that not only meets the rigorous requirements of the audit process but also puts you in a good starting position to make the case for credit.

For online classes not specifically designed to prepare for AP exams, there are respected institutions that schools look to for help in assessing their quality. For example, check out educere.net, which is used by many districts throughout the US to provide courses not offered through their schools. This and similar portals review online courses according to their own set of strict criteria.

Track record. There are two different types of track records to look for. Obviously, you want a program with a history of excellence. When you find one with core people and a curriculum that have stood the test of time, you know you’ve probably found a quality provider. In addition to looking for longevity, ask to speak with parents of current and former students. Ask about alumni. It’s nice to hear that this one went on to Harvard and that one went on to Yale, but let’s get real. These might have been smart kids who would’ve done that anyway. The real question is, what more have these students been able to accomplish as a result of taking this online course that they would not have otherwise? When an online provider can stand up to this kind of scrutiny from you, they are more likely to do the same when being considered for credit by your child’s school.

The second kind of track record is whether or not the provider has successfully assisted parents in getting their online courses accepted for credit. While the exact process will differ from school to school, the essence is likely very similar. School personnel need to be persuaded that the online course material meets their standards for the credit you are seeking. Just like with a good attorney, experience goes a long way when offering proper counsel to parents on what evidence to present to whom. Think of it this way. If you’re on trial, do you want a lawyer whose past clients are all in jail? I think not.

Find an ally. No matter the course, when trying to receive approval for credit, you absolutely need to find someone at your school who is forward looking to discuss this with. It could be a guidance counselor or other administrator. Ideally, it would be someone who’s handled similar situations before with positive outcomes. This is the person who is going to help you navigate the path to approval. If you’re fortunate, the process might involve meeting with the appropriate decision maker from the school; sharing detailed information about the course curriculum, online provider’s history, and any official stamp of approval from an authoritative body; and presenting examples of your child’s work, including scores and grading methodology. More typically, you’ll need several meetings with the same or more people to address follow-up questions and requests for additional information. As you might imagine, it behooves you to keep a detailed file right from the beginning, and also to be nice. Not a pushover, but definitely nice.

Communication. So you’ve presented your file full of evidence, and your school is still not sure about whether to give your child credit. What do you do? It may be time to step back from being the information middleman and let the educators talk directly to each other. Do your part to introduce and facilitate communication between your school’s decision makers and the right people from the online course provider. That would be your child’s principal instructor (a quality program would have assigned one) or someone else who can speak intelligently and in detail about the course curriculum. If you are successful in gaining credit for the online class, then counselors or administrators at your child’s school will want to stay in communication with you and/or the online course provider to get regular updates on your child’s progress. Communication is essential throughout this whole process, so make sure you choose a provider who is willing and able to make themselves and the necessary information available whenever they are needed.

What has worked for you in trying to get an online course approved for credit? Share your best advice here.

Maximize your credit with an IMACS course. Take our free aptitude test. Play along with our weekly IMACS logic puzzles on Facebook.

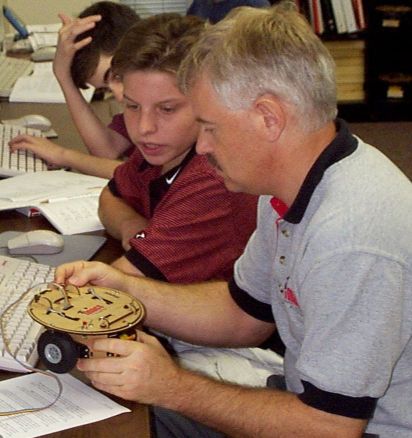

Iain Ferguson works with an IMACS student to program a mobile robot.

Today, we’re chatting with Iain Ferguson who – in addition to being IMACS’s senior curriculum developer for the computer science program – is the guy behind the sophisticated technology that runs our online computer programming classes. Iain has taught these courses as well, and so brings with him the experience of having seen what works in the classroom and what doesn’t.

Q: Why does your Introduction to Computer Science course use the Scheme programming language? Isn’t the Advanced Placement exam in Java?

A: We start off with Scheme because it’s the most effective for helping students to understand the fundamental concepts of computer science that are common to all programming languages. And we’re not alone in this choice. Graduates of the some of the top universities, including MIT, Yale, Princeton, Johns Hopkins and UC Berkeley, were first taught to program in their freshman year using Scheme.

What we’ve found over 20 years of teaching this course is that if you throw a new student straight into Java, or whatever language the AP exam covers at the time, he or she can easily get mired in its complicated rules of syntax. If you simultaneously try to make a student learn the fundamentals, which are arguably more important, some of those fundamentals just won’t be understood, or they’ll be understood incorrectly. And so the students try to move on to more complicated programming assignments, and they’re hampered by a false understanding of the underlying abstract thinking.

Scheme’s syntax is simple and natural. So it takes our students very little time to pick it up. They use their mental energy instead on developing a deep comprehension of the the abstract mathematical thinking involved in programming. Applying that way of thinking to concrete computer algorithms is then rather trivial for them.

Q: Beyond doing well on the AP exam, how do you know that this approach of teaching Scheme first is working?

A: We hear from a lot of our former students once they’ve gone on to university about how easy their classes are thanks to what and how they learned here. One of my favorite stories is of a student named Erik who went to Virginia Tech. He was taking Computer Engineering in a class of about 600 students, and the first exam was designed to weed out about half of them. So Erik completed the test in 10 minutes with a perfect score. The next day the professor called him in and accused him of cheating. Well, of course, he hadn’t cheated and when he said so, the professor gave him a similar question that was solved just as quickly. Then the professor wanted to know how it was possible for a freshman to have such a deep understanding. Erik told him about learning to program with Scheme, and that was enough to convince the professor that not only had Erik not cheated but that he was also the strongest student in this class of 600.

Q: If Scheme is so beneficial, why don’t more high schools offer it?

A: Their resources are very limited, especially in this economic environment, and the demands on teachers’ time is rather significant. As with most university-level courses, it’s unrealistic to ask high schools to even consider putting resources towards preparing and teaching a class like this. If you really want to do it at a high level, you need instructors with an extensive background in university-level computer science and extensive training in teaching advanced subjects to young adults. Plus you either have to develop the appropriate curriculum or find it and license it. So you’re looking at a lot of time and expense, both of which are, unfortunately, in short supply at the typical high school.

Sounds like a guy who knows his stuff! What language did you use in your first computer programming class, and did it leave you with confusion or clarity?

P.S. If you’re ever in South Florida and want to play a game of Nim, stop by our offices and ask for Iain. He will destroy you, and it won’t hurt a bit!

Make IMACS a part of your program. Sign up for our free aptitude test. Follow IMACS on Facebook.

Meet Katherine Wu:

• eIMACS Computer Science alumna

• Webmaster for the Hopkins Undergraduate Research Journal

• Lab manager for The Center for Language and Speech Processing where she will be conducting research this summer

• Author of “Breaking Barriers in Computer Science,” soon-to-be-published in the undergraduate research journal The Triple Helix

• One of only 50 students selected from across the US and Canada to participate in the Google FUSE 2011 computer science retreat

Are you suitably impressed? We are. When Katherine found us, she hadn’t even taken a computer programming for beginners class. But she knew what she was looking for – a solid introduction to programming and individualized instruction that would allow her to excel at a faster pace through more challenging material. Well, Katherine just sailed through her freshman year as a Computer Science major at The Johns Hopkins University, taking mostly junior and senior level CS courses along with a graduate level CS seminar, and is already deep into her summer research schedule.

When asked to reflect on her first year at college and experiences so far in CS, here’s what she said: “I was anything BUT picky about club and academic experiences my first-year in college. If there’s something you’re interested in doing, there are no ifs-ands-or-buts about it; take the chance and do it! If anything, you’ll always form new relationships and learn something new. I look back, especially on my experiences in Computer Science, and all I can say is ‘Wow! It’s like a whole other world.’ I took my first courses with IMACS, and they were the ones who sparked my passion in Computer Science and supported me all the way up through taking the AP Computer Science exam and beyond. I’m proud to say that IMACS is not just your typical course provider, but a community that strongly cares about your personal learning and achievements. I think they are one of a kind.”

Lucky for Katherine, the foundation she built at IMACS gave her the skills and confidence to handle upper-division coursework. Lucky for us, she’s happy to share her story (and even her video bloopers) with you. Check out her video below, and follow her summer research adventure here.

If you’re a former or current student or parent and would like to share your IMACS story, email us at info@eimacs.com.

Get a headstart on college with IMACS. Take our free aptitude test. Play along with our weekly IMACS logic puzzles on Facebook.

Why do we bother teaching children their ABC’s when they are so young? It’s not as if they are going to write the next Gettysburg Address once they know the difference between b and d. Why do piano teachers spend so much time with their beginning students on proper finger placement? It’s not like they are going to compose a symphony once they know that a treble clef means play these notes with your right hand. So why does IMACS start students off with an introduction to logic course? It’s not as though they’re going to solve the twin prime conjecture once they know the difference between modus ponens and modus tollens.

Now before you leave a comment about why that’s not a perfect analogy, you’re right. The point was to push your thinking in that direction before you think about this: Why do we use an exaggerated voice when talking to a baby that doesn’t yet understand words? Why do we toss off aphorisms to small children who don’t have the life experience to know what they mean? (Here’s a fun list if you want to practice sounding clever and wise.) It’s because when a growing brain comes to understand the nuances of tone, the subtleties of language, the connotations beyond the denotations, then and only then can its potential be realized as the developed brain of a novelist, journalist, and yes, even blogger unleashing the full power of human communication. Now, it’s a long time between teething and typing away at the next great idea. But parents still talk to their kids in these ways because they understand, if only subconsciously, that it’s part of teaching children how to express themselves effectively in adulthood. That’s likely how their own parents spoke, and so it’s very familiar.

Formal logic, on the other hand, is not as familiar. So the question naturally arises, “Why spend so much time teaching it when all I’m looking for are advanced classes for gifted and talented students?” For those who go on to major in math or computer science at college, the benefits of taking logic courses are obvious. They will be expected to write complicated proofs or programs that are logically coherent. If they choose these fields as professions, their ability to make a living (and stop mooching off of you) will largely depend on their ability to do this really well. And just as with teaching the skills that lead to great story-writing, you don’t start when the kid is already in college. By then, you want your college student to already have these tools so he can blow away the curve and make you so proud that you will not stress when he goes on his first spring break trip where there will be no mischief whatsoever. You start earlier by first teaching them how to craft a well formed and logically consistent argument, and then you layer on the advanced courses that require this fundamental skill in order to be successful.

But what about students who are not going into math or CS? Well, are there any future philosophy majors out there? How about pre-law? Wouldn’t you know it, they too will need the ability to make logically coherent arguments in their coursework, whether it’s debating the forms of Plato or taking the opposite side of a Supreme Court decision. Speaking of debate, we’ve had a number of high school students tell us that their logic skills helped them to excel in debate class. Come to think of it, if your child plans to be in a position where she needs to think about ideas in an orderly fashion, connect pieces of information together, draw conclusions from her analysis, and present her argument for scrutiny, understanding logic would be a huge advantage. Someone stop me now before I break out into “I’d like to teach the world a proof…”

Do you have a story about a situation in which understanding logic helped you? Leave it in a comment below.

Boost your logical reasoning skills with an IMACS course. Sign up for our free aptitude test. Follow IMACS on Facebook.

There’s an old Pink Floyd song that goes like this:

We don’t need no education.

We don’t need no thought control.

No dark sarcasm in the classroom.

Teacher, leave them kids alone.

Hey, teacher! Leave them kids alone.

If you don’t know who Pink Floyd is, go text your dad. If he’s old enough to know, then he’s probably of a generation where taking a class meant being in a bricks & mortar school, sitting in an intentionally uncomfortable desk, and listening to a teacher lead a mostly one-way lecture. If the teacher had to step out of the classroom, it would not be unusual for pandemonium to break loose and any semblance of learning to go out the door with her. So it comes as no surprise when some parents are skeptical that students can learn without a teacher being present in the same room. They just can’t imagine how online classes for high school students can work for their child. The reality is that online courses can work really well if you have at least three crucial ingredients:

Curriculum Experience

Experience matters, whether you’re talking about education, medicine, law, or any field where learning through doing makes a huge difference in the quality of outcomes. With online high school courses, as with traditional classes, curriculum experience is key. Remember that curriculum is not just about what topics are covered and in what order. It’s not just a list you can cobble together from Google searches. The best curricula are developed over extended periods with real student feedback and are time tested to have actually worked in physical classroom settings.

A good curriculum is also determined by how the material is presented. Are the lessons designed in an engaging way that invites the student to be part of the learning process? Or is it more like reading a lecture with a few colorful graphics tossed in? Having the experience to know how to pull students in can make the difference between a child who wants to stay focused on the lesson on screen and a child who is willingly distracted by the latest updates to their friend’s Facebook page.

Sophisticated Real-time Feedback

Okay, so now you think you’ve found a program with a good curriculum that has proven over time to be effective with real students. Next question: Can your child access the knowledge in a way that mimics the natural interactive style of humans? Or is he simply being shown a series of multiple choice questions without any catalyst to stimulate critical thinking? A good indicator would be if the technology, whether it’s a Web site or a software program, was developed to anticipate where students might stumble. This is another place where having taught the same curriculum to real students in a real classroom is a huge benefit to program developers.

Naturally, you will also want the technology to be designed with interactive features that provide immediate feedback to students when they need it. It would be like having a teacher right next to you saying, “Not quite, try again,” before you botch the rest of you work with an early mistake. Wouldn’t it have been great if when you were in school, you could find out right away instead of days later if your homework was wrong so that you’d have more time to correct your thinking before the test? (I hear you now, “That could’ve been me at Harvard!”) Speaking of tests, be sure that you have online access to your child’s scores for assignments and tests so that you and your child can monitor his progress.

Live Help Available in a Timely Manner

Sometimes, you just need a human touch. Like when you’ve exhausted the automated telephone menu and you just need to dial ‘0’ to reach the next customer service representative who will be with you shortly. Or in most cases, not so shortly. You’ll want to look for a program where each student is assigned a real instructor who monitors the student’s progress and is available for questions. Make sure that you can contact the teacher by phone or by email. The best programs have instructors and technical support available in some form seven days a week, including evenings. And if you do come upon a new situation that requires live help, program developers will be very thankful that you brought it to their attention because it helps them improve the online experience for you and future students.

Now that I finished writing this blog post, I have no idea how those Pink Floyd lyrics are relevant other than when the topic came up, the song popped into my head and now I can’t get it out!

What other features would you want to see from a provider of online courses?

Choose IMACS for a world-class online learning experience. Take our free aptitude test. Play along with our weekly IMACS logic puzzles on Facebook.

When students or their parents think about career choices for computer programmers, they often think of software development and gaming. No doubt, working for Google or Blizzard Entertainment would be awesome, but not everybody will land one of those coveted jobs. Operations research and various areas of engineering may also come to mind as places to put your programming prowess to work. Less frequently, however, do people think of the financial industry.

Now before you go ranting that these smarty pants are the ones who brought down the global financial markets with their esoteric models that only a Ph.D. could understand, let’s skip that debate and merely point out this fact: programming jobs in finance are challenging and pay well. Ignoring them because you think they are on “the dark side” simply leaves you with fewer options. So let’s take a look at three areas of finance where computer programming is more than just a peripheral activity.

Computational finance. Computational finance was historically the domain of math and science Ph.D.’s who moved from academia to Wall Street (“quants”), especially as the use of financial instruments such as derivatives increased. The work of pricing these complex securities was roughly divided between the quants, who came up with the methodologies, and the programmers, who implemented the mathematical models. Over time, the focus has shifted to refining and optimizing the models. According to the Wikipedia entry on computational finance, “[A]s the actual use of computers has become essential to rapidly carrying out computational finance decisions, a background in computer programming has become useful, and hence many computer programmers enter the field either from Ph.D. programs or from other fields of software engineering.” Programmers are no longer solely relegated to the IT department, on call to do the bidding of the brain trust. The best ones are now part of that brain trust and are considered essential to financial institutions’ ability to maximize profits and minimize losses.

Algorithmic trading. What is algorithmic trading? Let’s go to the Wikipedia page: “… the use of computer programs for entering trading orders with the computer algorithm deciding on aspects of the order such as the timing, price, or quantity of the order, or in many cases initiating the order without human intervention. … A special class of algorithmic trading is ‘high-frequency trading’ (HFT), in which computers make elaborate decisions to initiate orders based on information that is received electronically, before human traders are capable of processing the information they observe [emphasis added].” So one set of humans (i.e., computer programmers) creates mathematical rules to replace a different set of humans (i.e., traders). And they’re paid handsomely for this disservice to their fellow man. Maybe you can see yourself doing this as sweet revenge upon those evil trader dudes who, some say, blew up the financial markets. Not such a bad idea now, eh?

Actuarial science. Finally, actuarial science. Wikipedia, don’t fail me now! “Actuarial science is the discipline that applies mathematical and statistical methods to assess risk in the insurance and finance industries. … Actuarial science includes a number of interrelating subjects, including probability, mathematics, statistics, finance, economics, financial economics and [trumpets, please] computer programming.” Who knew that figuring out when a given cohort of individuals will, uh-hum, kick the bucket could be so interesting? Well, as it turns out, one of our former students knows this well as he was able to pass all of the actuarial exams at a fairly young age and is currently the chief pricing actuary of a major global life reinsurance company. We’re pretty sure he’s done well for himself.

So if you have a knack for computers and want to explore where these talents might take you, don’t forget about the financial industry as a place that can provide a rewarding career. Try to make room in your class schedule for the programming courses you will need to put you on the right path. If you don’t have access to these courses at your school, think about taking online computer programming classes. If done right, learning computer programming online can be just as effective in preparing you for the next level.

Do you or someone you know use computer programming skills in a non-traditional field? Tell us about it.

Open up your career possibilities with IMACS. Sign up for our free aptitude test. Follow IMACS on Facebook.

« Newer Posts — Older Posts »