Mathalicious blog recently posted a well-written and compelling article about the consequences of our nation’s sudden elevation of the popular video tutoring Web site, Khan Academy. If you haven’t read the piece, you absolutely should because it explains beautifully the key reasons why parents and school administrators should be cautious about jumping on the bandwagon of free, technology-based resources as a means of effective teaching.

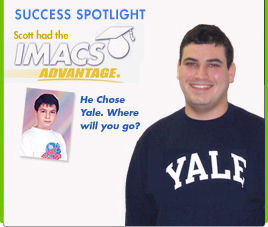

We won’t rehash here what’s already been said well by Mathalicious, nor do readers of this blog who like KA need to rally to its defense. IMACS acknowledges that KA is a valuable resource that has a place in the overall education portfolio for many students. But we also strongly believe that KA, or whatever the next free resource to be Web-ified is, is no substitute for high-quality curricula and the effective teaching thereof. This is particularly true for gifted and talented children.

Free Resources Are Good at Presenting Information and Sparking Curiosity

Children, bright ones in particular, are born self-directed and self-taught. As they enter school and progress through the regimented structure of age-based, test-driven instruction, it’s no surprise that this natural thirst for learning diminishes. For a gifted child this is intellectual torture, and the pain has only spread across our nation as budget cuts erode the quality of or eliminate altogether public school gifted programs. So it’s no wonder that many talented children and their parents have come to value a Web site like KA.

What’s not to like? KA offers a myriad of topics for a curious mind to explore. You pick which video to watch, and you decide when to move on if it’s boring. And KA’s founder, by most accounts, is pretty good at explaining concepts in a non-threatening way. For typical kids, this can be a superior alternative to classroom instruction. For gifted kids, this is a wonderful way to spark curiosity and access above-grade-level material. Those of us from an older generation are reminded of cherished times flipping through encyclopedia volumes, letting the books fall open where they may, and reading about some new topic that we’d never heard of before. Whereas the World Book cost parents a small fortune and took up a big chunk of bookshelf space, KA is free and fits on the smartphone in your pocket! So far, so good. Here comes the “but.”

Pedagogy Still Matters, Especially for Mathematically Talented Kids

But how does that spark become a burning fire of passion, dedication, effort, and tenacity—qualities necessary for a gifted child to achieve his or her full potential? A key component of the answer is teachers. More specifically, teachers who understand how to inspire bright children, who can guide them when they struggle, and who know how to unleash the power of their natural talent. Optimally, these teachers should be armed with higher quality curricula better geared toward kids who only need to be told things once. They should have the experience to know that the places where talented kids struggle are often different from the usual stumbling blocks for the general population, and they should understand that high-fliers sometimes need help in overcoming the fear of failure.

Nowhere is this more evident than in math where the abstract nature of its concepts and language call for an experienced and interactive guide. To a gifted child, the difference between one-way, rules-based, memorization-laden math instruction and student-involved, teacher-guided, reasoning-based interaction is like intellectual starvation versus a bountiful feast. The nourishing environment of the latter allows mathematically talented minds to devour, understand, apply, and sometimes grow the body of knowledge. No pre-recorded video that restates, however pleasantly, the usual instruction found in US math classes, with the added benefit that you can rewind and repeat for reinforcement, is going to elevate a mathematically bright child to the next level.

Bright Online Students Should Have Access to Supportive Instructors

At IMACS, we made a deliberate choice to use an interactive teaching approach that incorporates substantial student-led exploration guided by effective teachers. Our collective experience on how talented kids learn best, which questions they tend to ask, and where and why they tend to struggle has been gathered over decades of teaching our curriculum in a classroom setting. This wisdom has been painstakingly built in to our eIMACS online courses, which feature tools that provide immediate feedback at exactly the moments students most frequently need it.

Needless to say, a gifted child is wonderfully unique and creative. So it comes as no surprise to us that our students come up with questions from time to time that we hadn’t anticipated. This is exactly why each eIMACS student is assigned a principal IMACS instructor to answer these questions and provide individualized guidance when needed.

We know what you’re probably thinking, and yes, this blog post is self-serving. But it’s also what we genuinely believe because we’ve borne witness to the success of these ideas, having taught thousands of bright students this way over the years. As such, we feel compelled to share our experience with readers, especially parents and others who may be making decisions now or in the future on how to best foster mathematical talent (or any talent for that matter). As with coaching in elite athletics, effective pedagogy is essential to the full and fulfilling intellectual development of gifted children, and its value should not be discounted so readily. Don’t let talk of free videos convince you otherwise.

Looking for online courses in gifted math and computer science with top-notch teachers? Try IMACS! Take our free aptitude test. Solve weekly IMACS logic puzzles on Facebook.

“Indeed, your conception of failure might not be too far from the average person’s idea of success, so high have you already flown.”

– JK Rowling, Harvard commencement speech, June 2008

“People who have an easy time of things, who get 800s on their SAT’s, I worry that those people get feedback that everything they’re doing is great. And I think as a result, we are actually setting them up for long-term failure.”

– Dominic Randolph, Headmaster, Riverdale Country School, New York Times Magazine, September 14, 2011

Two weeks ago, the science world was abuzz with talk of a report that neutrinos seemed to have traveled faster than light. News of this finding traveled pretty quickly as well, as media outfits worldwide ran headlines that (gasp!) Einstein may have been wrong. News like this would have been dismissed summarily were it not for the fact that the research team involved in this experiment are not exactly a bunch of weekend armchair physicists. They are part of the OPERA Collaboration working at CERN.

So why would these esteemed scientists put themselves out there to be met by the inevitable wave of skepticism, even ridicule? Because they understand that if they made an error, opening their research to scrutiny in order to find and correct the mistake is exactly what will help them advance their work and the work of others. In fact, the official press release announcing these unexpected observations quotes CERN Research Director Sergio Bertolucci as saying, “When an experiment finds an apparently unbelievable result and can find no artefact [sic] of the measurement to account for it, it’s normal procedure to invite broader scrutiny, and this is exactly what the OPERA collaboration is doing, it’s good scientific practice.”

At IMACS, we couldn’t agree more, and would further assert that the same principle applies in mathematics and computer science. Learning to fail well in these subjects is particularly important because of their exacting and objective nature. Your proof is logically consistent or it isn’t. Your computer program compiles or it doesn’t. There is generally no interpretive latitude around whether you’re right or wrong. There is no arguing that the instructor’s subjective judgment based on his or her personal ideology caused your poor grade. Add to that the tendency of talented students to have a strong aversion to failure and you can see that how resilient one is in the face of failure will be a major factor in determining how much success one has going forward.

While we’re not experts in educational psychology at IMACS, we’ve taught thousands of talented children over the years and are parents ourselves, and what we observe is that learning to fail well is a “scaffolding” process. A talented child who is allowed to have small failures early on without harsh consequences and who is involved meaningfully in determining and executing corrective action shows greater resiliency when faced with the next level of failure. This process builds on itself as the child grows older and the circumstances and consequences become more serious. The failures may grow, but so does the child’s ability and confidence to handle them effectively and independently.

So parental readers, take a look at your mathematically or scientifically talented, award-winning, perfect-scoring children and ask yourself, at this age when the consequences of failure are not so great, are they developing the resiliency that will allow them to take the intellectual risks that are necessary for great success but may also lead to major failure? Do they know from experience, not from having you tell them, that they have it in themselves to bounce back? Ask of yourself, do I allow my child to feel safe about having small failures now so that he or she can rise up from a bigger failure later when I’m not always going to be there to pick up the pieces? If not, then perhaps it is time to lead by example and show that you can make adjustments with an eye toward the long term. After all, if your child is someday going to make the next groundbreaking discovery in physics, he or she should get a head start by learning to fail well now.

Have you heard a story like this before: My daughter used to enjoy math and science when she was in elementary school. She’s always been strong in those subjects. But now that she’s going into 7th grade, it’s no longer “cool.” She’s actually afraid that her classmates won’t like her anymore if they find out how talented she is. Her computer science teacher called to tell me that she doesn’t want to take the honors programming class next year, even though she was the top student in his class last year. How do I make her understand that she should pursue her natural talents regardless of what her so-called friends think?

There is no easy or single answer to this difficult parenting problem. The factors that motivate a child are often as unique as that child. But in our experience at IMACS, one factor seems to be pretty consistent across the board: In this age range, parental influence starts to wane, sometimes rapidly, and outside parties such as friends and teachers gain in influential power. If you don’t have buy-in from a tween or teenager on a particular idea that involves her, then you’re probably not going to get anywhere. In fact, there’s a good chance that the reaction you get is the exact opposite of the one you want. Such is the process of growing up. It just seems more painful to now find yourself on the parental side of this equation.

There are two broad pieces of advice that we can offer based on the anecdotal evidence we see and hear with our female students. One is to get your daughter involved in one of the growing number of programs that promote science, technology, engineering and math (STEM). The earlier you get girls excited about STEM, the better. Studies have shown that if girls are not interested by middle school, it’s almost impossible to get them to pursue any of these fields in college or as a career. Getting your daughter involved in math and science enrichment during elementary school is a great first step. Whatever the age, look for a program with a healthy proportion of female participants, or even a girls-only program if available in your area. When a girl is surrounded by other girls who are also interested in these subjects, then being a “math and science girl” doesn’t seem so “out there,” and the stereotype that STEM is for boys is less likely to be reinforced. Your daughter might also feel more confident and willing to take more risks in learning if she’s not surrounded by boys.

The other piece of advice is to find a trusted adult female who works in a STEM field to mentor your daughter. It’s important for girls to have STEM-minded peers, but they also need successful female role models to look to and learn from. We mean no disrespect to the many excellent male mentors out there, but there is no doubting the power of “seeing is believing” when it comes to convincing girls that they can have a successful future in STEM. And while it’s inspiring to read interviews with Google’s Marissa Mayer or actress Danica McKellar, building a positive one-to-one mentoring relationship with an accessible adult has much more impact. Your daughter can receive regular guidance that address the specifics of her situation (e.g., career options, scholarship applications, college admissions). Plus, it will be coming from an adult other than Mom or Dad who, at this stage of adolescence, have zero credibility.

Below, we’ve compiled a non-exhaustive list of organizations, programs and resources for encouraging and motivating talented young girls to get and stay engaged with STEM. Many have organized mentor matching services. If your daughter is approaching high school, we’ve also included two organizations that focus exclusively on high school girls. We encourage you to explore these links and to inquire further in your local communities for similar opportunities. Your daughters are counting on you, whether they know it or not.

Organizations that Encourage and Support Young Girls in STEM

National Girls Collaborative Project (NGCP) – The NGCP brings together US organizations that focus on motivating girls to pursue careers in STEM fields. The program directory currently lists over 2,000 organizations and programs by geographic location. Select “Mentoring” in the “Resources Needed” list to find programs that offer mentoring services. The NGCP Web site also has an extensive list of resources, including the NGCP newsletter and links to dozens of girl-serving organizations and Web sites.

Girls’ Electronic Mentoring in Science, Engineering and Technology (GEM-SET) – GEM-SET is part of the Women in Science & Engineering program at the University of Illinois at Chicago. The goal of GEM-SET is to connect young girls in middle school and high school with professional women mentors in the STEM fields. Girls must be affiliated with a partner organization.

Inspiring Girls Now In Technology Evolution (IGNITE) – IGNITE originated in the Seattle school district and has grown to include chapters around the country. The organization connects middle and high school girls with professional in STEM careers who act as role models and mentors. Programs also include job shadowing, field trips, career fairs, guidance for internship, scholarship and college admission applications.

Girls, Math & Science Partnership (GMSP) – The Carnegie Science Center in Pittsburgh sponsors this program for 11-17 year old girls. The main BrainCake Web site is designed to be totally cool, fun and interactive – so very now. Girls can also fill out a simple survey to be matched with a mentor.

Association for Women in Mathematics (AWM) – The AWM Mentor Network matches mentors with girls and women who are interested in mathematics or are pursuing careers in mathematics. Grade school and high school girls can apply. Mentors may be women or men, but students have the option of indicating a strong preference for a female mentor on the application.

Aspire – Aspire is the K-12 outreach program sponsored by Society of Women Engineers (SWE). The organization’s signature event is WOW! That’s Engineering where local SWE chapters bring girls and women engineers together to learn about and do engineering. You can contact your regional SWE section to find out if they will be hosting a WOW! That’s Engineering fair in your area.

Sally Ride Science – This organization was established by America’s first woman in space to support girls’ and boys’ interest in math and science, and to make a difference in society’s perceptions of girls’ roles in technical fields. Sally Ride Science sponsors one-day science festivals for 5th – 8th grade girls. Girls entering 4th – 9th grades may participate in hands-on science camps that provide an opportunity to explore science, technology, and engineering on the campus of some of the most prestigious universities. Locations for the summer 2011 included Stanford, Berkeley, UCSD, MIT and Caltech. The parent handbook includes very helpful information and advice on raising talented girls.

My Gifted Girl – My Gifted Girl is a community for gifted girls and women in all subjects, including STEM fields. They serve as a resource for parents, educators, mentors and other organizations that support talented girls and women. Free membership gives you access to My Gifted Girl message boards where mentors can answer posted questions and contribute in specific subject matter areas.

Looking Ahead to High School

National Center for Women & Information Technology (NCWIT) – The NCWIT Award for Aspirations in Computing recognizes high school girls for their computing-related achievements and interests. Winners are chosen for their computing and IT aptitude, leadership ability, academic history, and plans for post-secondary education. Just reading the profiles of past winners is an inspiring experience. They demonstrate that you will find talented girls from a variety of backgrounds and experiences no matter where you look across the country.

Digigirlz – Digigirlz is Microsoft’s program to give high school girls the opportunity to learn about careers in technology. The company hosts Digigirlz Days where students get to interact with Microsoft employees and see what it’s like to work there. They also sponsor multi-day High Tech Camp for girls at no cost.

IMACS students in a math enrichment class.

Former IMACS instructor, Brandi Parsell, offers advice on how to address the ultimate question in a way that stimulates logical reasoning and critical thinking skills.

It can be endearing, or at times downright frustrating – that eternal question, “why?”. When bright children discover that single word, they seem to grab onto it and won’t let go. Sometimes the answers are simple, and sometimes we find ourselves at a complete loss for words.

This innocent question, however, is a signal to parents that a child is ready to be challenged to think logically. The creativity is there – we can see it in their everyday play. It is how we encourage that creativity and shape it into critical thought that will form a solid basis for a child’s learning ability.

Critical thinking is one of the hardest subjects to teach older students; any schoolteacher will tell you so. But if you begin to give your children the necessary tools when they are as young as three or four years old, they can develop these skills more easily. When the question of “why” is put once again on the table, the best policy is to ask, don’t tell. Challenge your children; ask what they think the reason might be. Chances are you will be pleasantly surprised.

Often parents believe that when their child reaches school age, he or she will at last find satisfaction for that curiosity. Talented students, though, may become bored with traditional school curriculum. When such a student is not challenged to exceed our expectations, this frustration often takes the form of careless errors and lack of effort. If children begin to develop these kinds of bad habits, too often they give up quickly when faced with a truly challenging problem. It is important that bright students are encouraged to go beyond what is merely “expected” of them.

“Talented students owe it to themselves to stretch their minds as far as they can,” said Burt Kaufman, co-founder of IMACS. Burt spoke from experience. For over 40 years he worked closely with bright pre-college students and developed challenging mathematics curriculum materials to stimulate them to become true students – disciplined logical thinkers with an insatiable thirst for knowledge and understanding.

Parents are a child’s first teachers, and the best teachers don’t give away the answers. Turn your child into a detective, and yourself into their greatest source for clues.

An IMACS foundation in logical thinking sets students on a path to successful learning. Take our free aptitude test to begin your IMACS journey.

IMACS’ Director of Curriculum Development, Dr. Ted Sweet, discusses the importance of challenging the gifted and talented student in order to reach his or her full potential and to avoid common pitfalls. Ted is a graduate of Project MEGSSS, a predecessor program to IMACS. He completed his undergraduate studies at the University of Miami and his Ph.D. in mathematics at UCLA. Ted joined IMACS in 1998.

Burt Kaufman, one of the foremost American mathematics curriculum developers of the last half-century (and my high school mentor), once made an observation that resonates with many educators of bright and talented children. It was that good grades obtained through little or no effort ultimately led to poor study habits and general intellectual laziness.

Even parents of children enrolled in “gifted” programs of the type currently in favor with many public school systems sometimes complain that their child is “coasting” at school.

Unfortunately, students that solve every problem with ease often get out of the habit of focusing and thinking systematically, skills they will need if they are to reach their full potential. Not surprisingly, it can be a challenge for parents to explain to their bright children that getting an ‘A’ may not be enough to ensure their future academic success.

Bright students whose mental agility and intuitive cognitive abilities are not sufficiently challenged can start to develop problems during elementary school. These may manifest themselves in the form of so-called “careless errors” when doing arithmetical problems, for example. And talented students who have not been stretched intellectually will typically “give up too easily” when they finally encounter challenging problems that require careful analysis. In extreme cases, behavioral problems may start to develop.

The question of how to satisfy the intellectual needs of bright and talented children has been studied in depth by the professionals at IMACS. Our research demonstrates that bright students who are exposed to curricula that foster the careful, logical analysis of significant math problems benefit in many fields outside mathematics. A student who learns to truly think does not leave that skill in the classroom.

What classes that you coasted through do you wish had been more challenging for you?

Challenge yourself to be your best with IMACS. Take our free aptitude test. Follow IMACS on Facebook.

Guest blogger and former student, Natasha Chen, shares her experience on parenting a mathematically precocious child.

First, this is not a blog about how to tell if you have a mathematically talented child. There are many great resources out there by people more educated on and experienced in that topic. (I’ve found the Hoagies’ Gifted Education Page, and the book “Developing Math Talent” by Assouline and Lupkowski-Shoplik very helpful.) If you think you have a mathematically gifted preschooler, then you might have discovered that it’s hard to find a program for gifted children that caters to this age group. These are just a few tips I’ve found myself sharing with other moms of three- to five-year olds that you might also find useful.

Building Sets

LEGOs, Tinker Toys, Lincoln Logs, K’nex, Magna-Tiles, tangrams, blocks of all shapes and sizes. All of these and similar toys are great for stimulating different areas of mathematical thinking at different stages of childhood. First, you can play all kinds of sorting games. Group the red pieces over here. Group the square pieces over there. Oh no, what do we do with the red squares? We can put them in the middle! All the rest go on the outside. Voila, introduction to set theory. Then there is visual-spatial reasoning. Have you ever observed a preschooler building a structure? She’s often down on her hands and knees looking at it from this way and that way, trying to figure out where to put the next piece. Seems like a pretty good way to encourage the ability to envision objects from different angles. And a message to parents of gifted and talented girls from a former girl: We love, Love, LOVE these kinds of toys!

Mathematical Logic

This can sound so daunting at first. “How do you expect me to teach mathematical logic to a four-year old?” The answer is that you probably already do it every day without realizing it. Does this sound familiar:

Dad: “Your mom and I don’t play with the crayons, so either you or your brother drew on the wall.” Child: “Not me!” Dad: “So who was it then?” Child: “He did it!” Wait, wasn’t that just [(P or Q) and (not P)] implies Q?

Or how about this one:

Mom: “If you want me to take you to the park, you need to sit down and finish your lunch.” Child is still running around. Mom: “Okay, I guess we’re not going to the park.” So now we have [(P implies Q) and (not Q)] implies (not P).

Or worse yet:

Dad: “We’re cutting out junk food in our family. We all need to eat healthier.” Child spies Dad sneaking some barbecue potato chips. Child: “Hey, you said we couldn’t eat that!” Dad: “Uh, I’m not really your dad, so I’m not in the family?” Busted!

See, logic is really the underpinnings of childhood discipline. Hmm, let’s leave that one for a different blog.

Fractions

I’m sure we’ve all said something like this to our kids: “You can have half the cookie now and save half for later.” And then you wordlessly break the cookie in half in view of your child. If you cook or bake, let your kids observe and narrate as you go: “We need a quarter teaspoon of salt. Would you please pass me the quarter-teaspoon?” “Which one is it?” “The one that says one and then a slanted line and then a four.” “Why does it say that? Why did you call it a quarter? That’s a coin.” There’s nothing like parenting gifted children to keep you on your toes! If your child’s fine motor skills are pretty good, then get a plastic knife and let them cut up soft ingredients. Say, “Cut it in half, and then cut the halves in half so you get quarters.” It doesn’t matter if they cut accurately, just that they comprehend that we get fractions from dividing up a whole. Keep a set of measuring cups in the bath toy rotation, preferably ones with the amounts (e.g., 1/2) written in big numerals. If you have room, keep several sets so that you can take one cup of water and pour it into three different 1/3 cups. “Look at that! The first cup is empty now and the other three cups are all full.”

Lose The Lecture

As you have similar kinds of enriched dialogue with your little Fermats, keep in mind that at this age there is no need to make a big production out of any of these lessons. Little ones generally don’t have the patience for a mini-lecture, nor do they seem to really embrace new information delivered that way. Mathematically gifted and talented youngsters will welcome these experiences as part of rhythm of their lives. It just takes a little more conscious effort on our part as parents to disguise the learning as play.

If you have any more tips, please leave a comment. I could use all the help I can get!

Start the ball rolling with IMACS by taking our free aptitude test. Follow IMACS on Facebook.

Terry Kaufman with student at the IMACS Hi-Tech Summer Camp Open House.

Welcome to the IMACS blog. Check in with us from time to time for mathematical musings and more. Since this is our inaugural blog post, we’ll be utterly predictable and start with the obligatory interview with the president. No, not that president. We mean our very own Terry Kaufman, president, co-founder and all-around good guy, at the Institute for Mathematics and Computer Science, lovingly known as IMACS.

Q: So, Terry, why did you start IMACS?

A: My dad, Burt Kaufman, had been working with mathematically talented students for as long as I can remember, whether it was developing curriculum or teaching them in the classroom. The programs he was involved with ultimately brought him back to South Florida where the Broward County public school system agreed to fund what was then called Mathematics Education for Gifted Secondary School Students (MEGSSS). Project MEGSSS had a successful run in Broward County from 1983 to 1993, but then fell to the budget cutting axe. Well, my oldest child was only two at the time, and I thought to myself, “You know, I really want him to have the benefit of this curriculum.” I’d seen with my own eyes the enthusiasm for math and computer science that my father’s students had when they studied this material. So I said to Ed [Martin] and Iain [Ferguson], our senior curriculum developers for math and computer science who were also teaching MEGSSS students at the time, “Let’s find a way to keep this thing going.” And IMACS was born, really out of a parent’s wish to have high quality math and computer science education available to his child.

Q: What’s the latest news at IMACS? What big goals are you and the team working towards?

A: We’re always working on new online computer courses. One initiative that we’re really excited about is our Online Virtual Robotics Lab in which students program robots in a virtual world. It’s entirely Web-based, but the actual physical behavior of real robots is accurately represented, even the appropriate laws of physics. What we’ve put together is a learning environment that integrates science, technology, engineering and math skills in a very natural way. Several schools are already using it as part of the national STEM Initiative, and we expect that number to grow.

Another of our programs that comes to mind is ISLAND, which stands for Interface for Scientific Learning & Natural Discovery. Here we use computer simulations and some really innovative online activities to encourage students to think scientifically and get involved in the learning process. Rather than simply being told dry scientific facts, they learn by doing – making hypotheses, observing simulations, and then developing scientific theories. They’re so engaged that they don’t realize they’re learning the required state standards. You know, people have traditionally thought of IMACS as a place for gifted and talented students, but the truth is that our teaching philosophy is really applicable to all students. With ISLAND, it’s been very gratifying to be able to share the benefits of our unique approach with a wider audience.

Q: Any message for the lucky folks who stumble upon this blog?

A: Yes! Read it. Share it. Tell us what you think. We are listening. There’s such a strong sense of community among our students, parents, teachers and alumni; it’s time we share that enthusiasm online. Obviously, we’d love for this blog and our Facebook page to be go-to places for people interested in taking online computer programming classes. But more importantly, we know from our many years of teaching mathematically talented students that we have a huge amount of knowledge in our heads on how to bring out the best in them, how to help them reach their full potential. Why keep it there? And we also know that our parents and students have great advice to give too. They share their stories with us face-to-face or in letters all the time. Now there are at least two places where these stories can find a wider audience and maybe help someone who is searching for this kind of information.

If you’ve read all the way to the end of this blog post, then our first attempt couldn’t have been all that bad! Do you have a topic to suggest for our blog? Leave a comment.

Find out if you’re ready for the IMACS experience. Sign up for our free aptitude test. Follow IMACS on Facebook.

« Newer Posts