(Este blog tambien esta disponible en Español.)

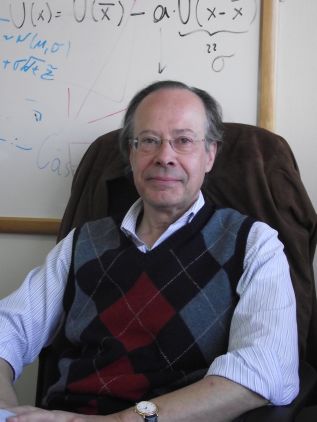

This week, IMACS asks Dr. Arturo Cifuentes to share his colorful opinions on a variety of topics. Dr. Cifuentes received his Ph.D. in applied mechanics and M.S. in civil engineering from Caltech. He spent five years at the prestigious IBM Thomas J. Watson Research Center. Dr. Cifuentes then moved to Wall Street, where he spent 15 years working in the fixed income market. During the recent financial meltdown, he was invited to testify before Congress as an expert witness on the subprime crisis. Dr. Cifuentes is currently an Adjunct Professor in the Department of Industrial Engineering at the University of Chile and writes a monthly column for El Mercurio.

As you were growing up, what made you realize that you had a talent for math and science? How did you become interested in pursuing degrees and a career in engineering?

My father was an engineer who did a lot of consulting work. He enjoyed very much what he did and talked quite often about the “problems” he was trying to solve. I found that fascinating. I think, in a way, that enthusiasm motivated me to investigate in more detail what he did. And I liked it.

Also, having early access to all the books by Yakov Perelman was a turning point in my life. Those books were fun to read, intriguing, and very powerful and persuasive. My father did not believe in libraries; he felt that any book worth reading should be at home. The fact that I had access to many books since I was a child was fantastic. And the Perelman books convinced me (I am still convinced) that any career in science or a closely related field could be rewarding and interesting.

In your opinion, what needs to happen with math and science education in the United States in order for US students to remain competitive globally?

Parents should turn off their TVs, buy more books, and tell their children the truth: Sure, learning something like math or physics can be a lot of fun and can be rewarding, but it involves a lot of hard work and effort. And if those who believe in Intelligent Design could be persuaded otherwise, that would be quite helpful.

Two tendencies, or perhaps ideas, which in my opinion are pretty bad and should be eliminated, are the following (and I acknowledge that most people will disagree with me here):

[i] The growing emphasis on group work and team effort. Learning something like math is pretty much a lonely effort, a solo journey. People have to accept that. There is nothing wrong with team effort (soccer, for instance, is about that). But certain things (playing the piano, for example) require a lot of NON-group work. Math is one of those things.

[ii] Computers in the classroom. There is nothing wrong with using computers. But introducing them at an early age (with the idea of making learning fun) is a disaster. Children must learn to think conceptually first. And when introduced to computers, they should learn how to program them instead of learning how to react via a mouse to some external stimulus.

Now that the space age seems to be coming to a close, what is going to be the stimulus for intellectual and scientific pursuits going forward?

Well, in science and technology, whenever a door closes, several windows open. The advances in genetics, bio-engineering and neuroscience are very exciting; the same with computer science and communications. In physics, whoever manages to reconcile relativity and quantum mechanics will be the new Einstein (or Newton). Not to mention many more practical problems that still remain unsolved: earthquake prediction, for example.

You are a voracious reader. What book or books would you recommend to today’s students and why?

I was fascinated by Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn when I was a teenager. I read them in Spanish, and they were as good as in English. I also read Kafka, Cortazar, Hesse and Poe. Unfortunately, Etica para Amador by Fernando Savater is not available in English. I think every teenager should read that book. Finally, Richard Feynman’s Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman is a must. If anyone thinks science is boring, this is the book to read.

How did you go from doing structural engineering research on thermal stress and circuit boards to analyzing complex financial securities?

I had been working at IBM Research in New York for five years, doing a lot of interesting stuff, and never thought about going anywhere else. Unfortunately, IBM was having a difficult period and they decided to cut costs. That meant that instead of using 100% of our time and effort to do research, we were supposed to go out and find funding (i.e., write grant proposals, etc.). The minute I saw the first few forms and all the paperwork involved in getting a government grant, I was done. I decided that I was not going to spend the rest of my life begging for money. That took the fun away from the research.

I loved (and still love) New York, and my wife had a good job there, so I decided to stay there and look for work. I quickly became aware that there were not many options for scientists in the New York area. Fortunately, a friend who worked on Wall Street asked me if I would consider interviewing with his firm.

“I don’t know anything about finance,” I said.

“As long as you can do Monte Carlos,” he explained, “you will be fine.”

I knew Monte Carlos. And in a few weeks I moved to the financial field.

But at the end of the day (as bankers like to say), it is all the same: thinking analytically and logically about problems. If you have a good background in math, it is easier to jump from one field to another. You learn to quickly identify the essentials and then the math helps. The key is to acquire good quantitative skills when you are young; you can easily learn the rest later. But if you don’t get your math tools under control by the time you are twenty, it is probably too late.

You currently write a column on business and economics, and you previously wrote an opinion column reflecting your varied interests in topics such as soccer and travel. Technical people are often stereotyped as having narrow focus and weak communication skills, so to what do you attribute your broad range of interests and abilities?

When I grew up I never had that impression. (I mean, that technical people had a narrow focus.) My father, who was a civil engineer, spoke several languages, and he often quoted Shakespeare in English and Goethe in German. He had a great library at home and read a lot. And his interests were very wide. I remember one Saturday (many years ago, I was ten or twelve probably) we went to his favorite bookstore and came back with three books: one dealing with humidity in high rise buildings and how to control it; a second book was about the evolution of financial markets in Chile; and the third book was about Freud. I still remember what the salesperson said: “I have seen many people buying these books before, but I have never seen the same person buying all three!” Well, that was my father. He was a very important influence and example when I grew up. He was a guy with many interests and skills. I owe him a great deal.

Any parting words of advice to the students and parents who are reading this?

When you are older than fifty, you tend to give more advice than you should. So I will be brief: Do what you like and follow your instinct. And remember, life is not about career choices or promotions. It is about love and friendship. Nothing else matters. Although having good math skills is always a plus.

Students worldwide take IMACS classes online. If you’d like to find out more, sign up for our free aptitude test or contact IMACS at info @ eimacs.com.

Leave a Reply